Operation Fermentation – Transform your food – Fermentation is for everyone

Our personal story

Walking to school in the mid-fifties in Untersteinbach, a small village with around 800 inhabitants, Hans passed the local dairy, where farmers left their milk to be made into butter and quark, a further 100 meters on and he could smell the freshly baked sourdough breads, made from grain milled locally with the power of the river meandering through the village. The butcher made wonderful salamis besides other meats and sausages from cattle, sheep and pigs grazing the fields and there was also a winery, which transformed the grapes from the south facing hills into Riesling, our “house wine”.

After school Hans had to help his granny in her grocery shop, where one of his tasks was to fetch sauerkraut from the barrel in the cellar below the shop for her customers. Most of the sauerkraut was produced in the village as part of a communal sauerkraut making event in the Autumn.

Gaby, growing up in Frankfurt, would often buy sauerkraut on her way to school.

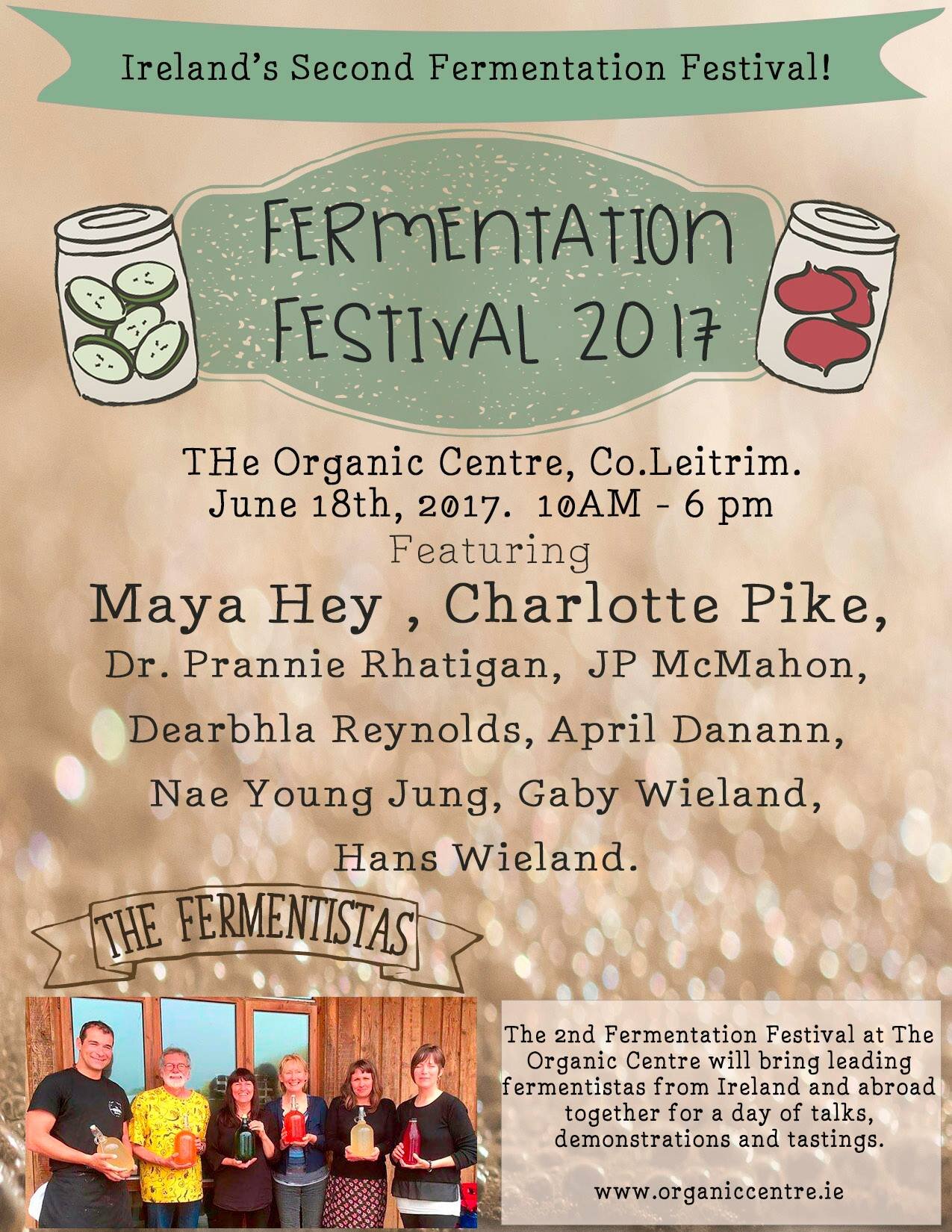

Little could we have imagined at the time, that growing up in a food culture based on fermentation and eating all these “normal” foods at home would led us to organise the First Irish Fermentation Festival at The Organic Centre in June of 2016 with a second to follow in 2017.

We are not telling this story for nostalgic reasons, but to explain and demonstrate the deep connection of fermentation, food production and village culture. Fermenting food was part of our daily life, of ordinary people’s lives. This was more than 60 years ago and it amazes us how today the whole culinary world talks about fermented foods as if it had been discovered only yesterday.

One of our missions in life is to make fermenting food part of our daily lives in the same way as growing some vegetables, cooking a dinner, composting or brushing our teeth. Fermentation is for everyone, seducing good bacteria to help us preserving food is fascinating; it empowers us and makes us all producers. We hope this article will help you to become a Fermentista!

Fermentation – Fad or fab

Fermented foods have become trendy and the latest “new” thing on the menu of many restaurants, including high profile establishments, and many chefs in the wake of the “New Nordic Cuisine” create dishes with fermented ingredients.

Fact is, fermentation is a natural phenomenon and has been in the food repertoire of human beings for thousands of years. I believe the new fascination with fermented foods is probably that they bring together an ancient tradition with our current obsession with healthy eating.

By some estimates as much as one third of all food eaten by humans today worldwide is fermented. Fermentation can turn fruit juices into wine, soaked grains into beer, milk into cheese, water and flour into bread and cabbage into sauerkraut.

We eat and drink fermented foods everyday: coffee, chocolate, yoghurt, salami, pickles, vinegar and wine. We seem to like them without thinking too much about how they are made.

Although sauerkraut - German for "sour cabbage" - is thought of as a German invention, lacto-fermented cabbage was already known in China some six thousand years ago. Shredded cabbage fermented in rice wine was served as a staple food for those who built the Great Wall of China.

Captain Cook’s sailors were fed fermented cabbage on their voyages, since it was well known at that time as an effective way to prevent scurvy.

Fermentation is preservation

Fermenting is just one way of making fresh food last longer and besides storing and drying it is one of the oldest traditional methods of food preservation compared to the more recent industrial methods of canning through pasteurisation and the more modern of freezing.

I want to concentrate here on fermenting vegetables through lacto fermentation and inspire you to transform the bounty of your garden into your own super foods for the time, when fresh produce is not available through the Winter month.

The act of fermenting vegetables is often as easy as chopping or grating a vegetable, putting it in a glass jar, add some sea salt, pour in good filtered water (Please note that chlorinated water can inhibit fermentation!) and wait. Fermenting vegetables does not need starter cultures, as the good bacteria come with your vegetables or are airborne or already living in your kitchen. We are talking wild fermentation here in contrast to cultured fermentation as in cheese making, using specific strains of lactic acid bacteria.

Fermenting vegetables in your kitchen does not require expensive or unusual equipment, all you need is a knife, a chopping board, a bowl and jars. Fermentation does not need electricity, neither for making your ferment nor for storing. Fermented foods are safe, because they are sour (see “Acidification” below).

Examples of traditional fermented vegetables include not only sauerkraut and kimchi, but pickled cucumbers, red cabbage, carrots, radishes, and beets.

From GIY (Grow it yourself) to FIY (Ferment it yourself)

Most importantly, fermenting your own vegetables puts you in control as it has become standard practice for commercial producers of sauerkraut and other fermented vegetables to pasteurise their products, or to add chemical preservatives to increase their stability and extend their shelf life, which defeats the whole purpose of fermentation.

Production Process – How does fermentation work?

Traditional lacto-fermentation relies on naturally occurring beneficial bacteria, the Lactobacilli, which are similar to cultures used to make yoghurt and sourdough bread. Lactobacilli feed on sugars (fructose) in your fruit and vegetables and break them down to produce lactic acid, which acts as a natural preservative.

“Acidification mostly through lactic acid bacteria is the primary means of food preservation by fermentation.”

Acidification

• Makes foods resistant to microbial spoilage

• Makes food safe against pathogenic bacteria

• Preserves food between harvest and consumption

• Modifies the flavour

• Improves the nutritional value

(Keith Steinkrauss)

Firstly fresh fruits or vegetables are washed and cut into pieces. They are then mixed with a small amount of sea salt, which draws out the juices and helps to preserve the fruits or vegetables while the fermentation gets started. The mixture is then packed into airtight glass jars or fermentation crocks and left in a warm place, which is your kitchen at around 18 to 20 degrees Celsius to ferment. The final acidity at the end of a successful fermentation process effectively inhibits pathogenic bacteria and preserves the vegetables for out‑of‑season use.

One of t he most important golden rules of fermentation is:

Keep your fermented vegetables immersed in their own juice or in salt brine at all times!

Once the initial fermentation is finished and the desired acidity is achieved the ferments can be left in the jars or repackaged from the big crock into smaller airtight containers. Ferments are normally stored in your cool larder at 10-12 degrees Celsius.

Fermentation is transformation - The health benefits

The health benefits of lactic fermentation are numerous: It improves digestion by breaking down certain types of carbohydrates that can be difficult to digest. It stimulates the immune system and helps to detoxify the liver. Because it does not involve cooking or heat treatment fermentation preserves vitamins and enzymes and often creates new vitamins, like vitamin B12, which helps regenerating red blood cells. Fermented vegetables are often higher in vitamin C than their raw ingredients and very low in calories (e.g. 100 g of Sauerkraut has only 20 calories).

The most important health benefits of fermentation lies in the probiotic bacteria, which are good for our gut. There is new research published nearly every day about the importance of our Microbiome, the community of microbes and bacteria living in our gut, and how important probiotic foods are for our general health and well-being.

The Power of Probiotics:

Probiotics are beneficial bacteria and microorganisms that live in our gut and aid digestion, help to absorb nutrients from our food and boost our immune system. The majority of these living organisms live in our large intestine and form a neural network that is often called our “second brain”, hence the term “gut feeling”.

The following recipes are courtesy of Gaby Wieland from Neantog Kitchen Garden School in Cliffony, the pictures are courtesy of Siobhan Morris, food consultant.

Kim-Chee is an easy and quick way to start fermenting vegetables, as you can eat your ferment after a few days. Sauerkraut ferments for 10 to 14 days and should let mature for at least 6 weeks (in my opinion), stored cool and dark it keeps for up to 9 month. Beet Kvass is an easy way to start fermenting in a salt brine.

Sweet and Spicy Kimchi

• 1 Napa or Savoy or white cabbage, finely shredded

• 3 Carrots, finely shredded

• 1 Cucumber, de-seeded and finely shredded

• 1 Bunch scallions, thinly cut into diagonal pieces

• 1 Apple, finely shredded

• 1 Orange, peeled, sectioned and chopped into small pieces

• 2 garlic cloves, minced

• 1/2 teaspoon, cayenne or fresh hot pepper

• 2 tablespoons sesame seeds

• 2 teaspoons sea salt

• Shred the cabbage (Picture 2) and put in a large mixing bowl with salt and gently massage to release the cabbage juice (Picture 3). Do this several times.

• Add the remaining ingredients and mix well (Pictures 4 and 5).

• Firmly pack the vegetable mixture with the juice into a gallon glass jar (Picture 6). Cover with a big cabbage leave and place a small glass jar, filled with water on top of the veggies to keep them submerged in the liquid while fermenting.

• Cover with a clean tea towel or muslin and store in a warm dry place (your kitchen) for 2 to 4 days. After 2 days check flavor, and if it's to your fermented taste, you're done. If you like more tartness let it go for another day or two and check again. (Once opened store in the fridge.)

Koreans eat so much of this super-spicy condiment that they say “kimchi” instead of “cheese” when getting their pictures taken. Kimchi is loaded with vitamins A, B and C and probiotics (Picture 7).

Sauerkraut

• 1kg of cabbage (variety: Filderkraut or other cone-shaped varieties)

• 1-2 teaspoons of sea salt

• Herbs and spices (5 cloves, 1 bay leaf, 10 black peppercorns, a few juniper berries)

Preparations:

• Grate cabbage or slice very thinly with a knife.

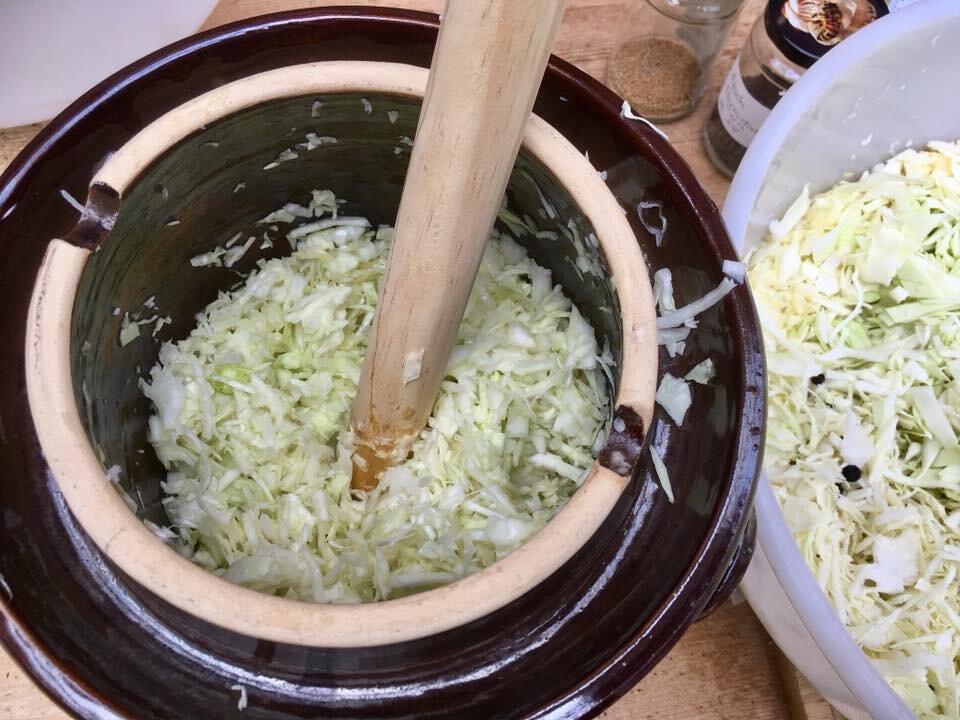

• Fill a heavy duty glass jar in layers, pounding the cabbage with a wooden spoon adding the spices now and then and sprinkle the salt on each layer. Pounding and crushing the cabbage will release juice, keep going until the juice is floating 1 cm deep on top of the cabbage. Cover the top layer with a big cabbage leave and weigh down with a small glass jar filled with water or a ramekin (see Picture 8)

Fermentation stages:

• At 18-20 degrees Celsius in the kitchen for 10-12 days.

• It will start bubbling after 2 days and stop after about 10 days, when initial fermentation is finished.

• Store cool at 10-12 degrees Celsius for at least 6 weeks before consumption.

Fermented foods may have an acquired taste, because they are sour. The acidic flavours can be gentle or intense, according to the recipe. Sauerkraut can be eaten raw or (in the Winter) gently heated (below 40 degrees Celsius) in a little melted butter with chopped onions and a few slices of apples. Non vegetarians enjoy sauerkraut with sausages and bacon, best served with mashed potatoes.

Red Beet Kvas

Ingredients: 1kg of beet, a piece of ginger, 1 teaspoon of sea salt, filtered or spring water

Method: Clean the beets and chop into quarters

· Add chopped beets, ginger and salt to a 1 litre glass jar

· Pour the water in and cover with air-tight lid or airlock

· Ferment for 4-10 days, strain the liquid into a glass bottle and chill before drinking.

From left: Beet Kvass, Daikon radish kimchi, Sweet & Spicy kimchi. Butternut squash for hummus.

Here is the basic recipe for fermenting vegetables in salt brine (as used for the Red Beet Kvass)

Please note that chlorinated water can inhibit fermentation. Use filtered water or spring water.

Fill vegetables, spices and salt (ideal salt concentration is 3-4 %, 30-40g of salt for 1 litre of water) into glass jar, and fill in enough water to cover vegetables. Leave 2 cm space between vegetables and lid and close tightly. Leave in a warm place for 10 days. After 2-3 days it starts to ferment und you see some bubbles appearing. Move jar to a cool place after 10 days. Vegetables are ready to eat after 5-6 weeks.

Fermentation

is a preservation technique

increases nutrient content in certain foods and

is good for the gut

Hans and Gaby Wieland have been fermenting vegetables nearly all their lives, they have been organic cheese makers, sourdough bakers and kombucha and kefir brewers. They teach fermentation classes since 1997 at Neantog, their farm near Cliffony, Co. Sligo and elsewhere.

For more information on courses, workshops and talks contact them on 087 6122082, or Neantog@gmail.com, also www.neantog.com